|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|  |  |  |  |  |  | By Rowland Barber

In 1967 they were shooting a movie called “Doctor Dolittle” here on the Century Ranch, 20th Century-Fox’s craggy redoubt in the Santa Monica Mountains. Rex Harrison, in the title role, made such a thing about “talking to the animals” that one of the animals, a monkey, apparently had it up to here with enforced integration and escaped from the set, scampering off into the chapparal above Malibu Creek. The runaway monkey has never been seen since. Today, seven years later, they are shooting a television series called Planet of the Apes here on the Century Ranch. This time they are taking no chances, and all the simians in the show are humans dressed up in monkey suits. So far, not one of them has escaped. The prime deterrent has not been a watchful keeper, but a minimum day’s pay of $148 plus over-time plus 15¢ a mile for travel.

The reason everybody is here, gravely doing a lot of things that would otherwise be ludicrous, except on Halloween, is that 20th Century-Fox has found the 40th Century Ape to be big box office. The anthropomorphic primate has been that studio’s biggest source of continuing revenue since Shirley Temple. The original “Planet of the Apes” film, plus its four sequels—“Escape from,” “Beneath,” “Conquest of” and “Battle for”—have sold over $160 million worth of tickets. Now, in its TV version, the property could net Fox—and CBS—yet-to-be-counted millions more.

And that, for all you husbandry majors up at State College, is how you milk an ape.

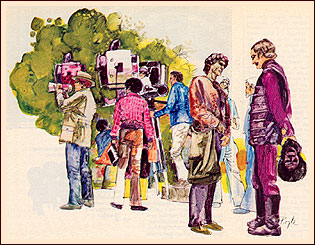

The assistant director calls for quiet on the set, which is the barnyard. Behind the garish array of camera, cables, mike booms, arc lights and shiny-boards, director Don Weis surveys the scene to be shot and says, “Release the chickens—stand by to cue the gorillas—and—action!”

The Chicken Wrangler opens his cage and shoos half a dozen dazed hens into camera range. Also in range are a chimp farmer, the farmer’s chimp wife, and their chimp children; Our Heroes, astronauts Alan and Pete (played by Ron Harper and James Naughton), and Our Heroes’ guide on the far side of the time warp, a friendly chimpanzee named Galen (played by Roddy McDowall).

Here’s the story. The farmer has been persuaded by Galen to give refuge to the astronauts, who are being hunted down by henchmen of Urko, the gorilla who is Chief Enforcer in the apes’ police state. The boys from the 20th century are red-hot subversives to Urko and his ilk, since they hold the secret of man’s past glory on the planet, a secret that the apes have suppressed in order to keep their slave labor force of humans in check. Alan and Pete want to hang around the chimp farm for a while, in the guise of “ordinary” humans, so they can perform their Good Deed of the Week, which this week is helping a cow give birth.

On cue, three mounted gorillas, rifles at the ready, gallop into the barnyard, raising a cloud of dust. They are mean incarnate: prognathous, sunken-eyed and hairy; hulking studies in black-on-black. For some reason they are dressed in leather jerkins, gauntlets and boots straight out of the Sheriff of Nottingham’s posse in a Robin Hood movie. (For some other reason, the humans of the planet are gotten up like Biblical rabble out of a Cecil B. DeMille movie. There are all kinds of time-warps in operation here.)

|

|  | Director Weis is unhappy with the movements of the chimp Galen. “Cut!” he calls, and the Chicken Wrangler rounds up his flock and drops them, fussin’ and cluckin’, back into the cage, and the three gorillas wheel their mounts and ride back to the shade, where the Horse Wrangler takes over the reins.

His arm on “Galen’s” shoulder, Weis says, “Roddy, I wonder if—when you first see the gorillas riding up—” He is interrupted by the voice from deep inside the chimp mask: “Excuse me, but I’m not Roddy McDowall. I’m Roddy’s double.”

|

|

|

“Oh. Right,” said Weis, recovering quickly. “Now, in this shot, you’re fairly close on camera, so I wonder if you could—you know—twitch your nose more, like Roddy does?”

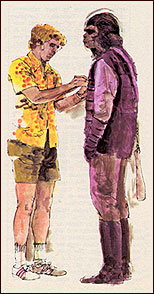

Ron Harper fished a tobacco pouch from out of the folds of his Barabbas-like sackcloth, filled his pipe, lit it, and said: “Telling the apes apart here is a problem for somebody new on the set. But after a while you learn to recognize them by body shapes and their quirks of movement. See that gorilla getting a makeup touch? Tom! Hey, Tom—!”

The gorilla, unheeding, walked away. “Sorry,” said Harper. “So it’s not Tom. Well, I know it’s not Ronnie, so it must be Eldon.”

Curious as to how this unintentional but cruel alienation had damaged the psyches of the TV apes, I wandered about the set between takes to see what might be preoccupying them when they weren’t on camera. Four gorillas were lounging under a thatched lean-to. One gorilla was reading Daily Variety. The second gorilla was doing needlepoint. Gorillas Three and Four were engaged in an intense conversation. A-ha! G-3: “I just made a pretty good buck doubling for Steve McQueen.” G-4: “Yah? Nice goin’. I just did a Volkswagen commercial.” G-3: “Neat.” G-4: “And I still got a Pabst Blue Ribbon running.” Gorilla 2, putting down his needlepoint, picking up on a long-lapsed conversation: “I still say, what’s the point of living out here if you don’t have a swimming pool?”

|

My in-depth ape analysis was interrupted by the break for lunch. Humans—crewmen, astronauts and slave laborers—headed for the chow wagon, some 300 yards away in a grove of live oaks, in a stampede. Chimps and gorillas trudged in their dusty wake, shedding costumery as they went, stripping down to T-shirts, tank tops, bare chests and, in one memorable case, to a bikini bra. They were all grateful for the break, but in no hurry to endure the ordeal of lunch.

|

|  |  |

|

More than the intensive heat, the melting makeup, the flies, or the interminable stage waits, hunger is the bane of the thespian ape’s existence. The mask—or “appliance,” as they call it, out of respect for the hinged jaws—is built on, section by section, during the three-hour makeup session, after which the hair is laid on strand by strand. Once on, the appliance is on for the day. While the mandible can waggle enough to simulate talking, it does not open wide enough to accommodate a normal mouthful of food. A further gnathic hazard is the three-inch gap between the protruding ape teeth and the actor’s own teeth.

So most of them settle for milkshakes, soups and eggnogs, taken through a straw. A few of the more enterprising apes manage to maneuver flat spoonfuls of food into their mouths with the aid of a makeup mirror. But this is very tedious. It is also dangerous. As a gorilla who had gone back to milkshakes explained: “You drop a glob of macaroni salad down inside your appliance, and the flies find it, it’s sheer torture for the rest of the day.”

The company is moving right along, on schedule (six days per episode) and budget ($200-300,000 per), and producer Stan Hough is pleased. Hough is a big, sunny, non-artsy movie hand, up from the ranks of 20th Century assistant directors, who still wears the badge of his old calling—a red duckbilled cap. He also squints a lot, which gives him an appropriate into-the-future look.

“It’s not only that actors have a ball playing something totally different, in their masks and costumes,” Hough said, “but we have so much latitude in what we can say, dressed up in monkey suits. We are enjoying the freedom, the fun, of creating a whole culture and society from the ground up. We can reveal truths and show things we could never otherwise get away with. Make social statements. About the violent side of human nature. About the horrors of the police state. About the blindness of prejudice. Let’s face it. What we’re doing is playing God.”

Unfortunately, it’s hard to play God on a six-day-bike-race of a production schedule, and the criterion of Creation’s progress is “How many pages did we shoot today?” As a result, there is a surfeit of Jungle Jim “action” shots, skulkings around corners and dartings from bush to bush to the adrenalin music of tom-toms and muted horns, and a modicum of Truth Revealed.

On a later visit to the small planet in the Santa Monica Mountains, the set-side fun and games were noticeably subdued. The Nielsen ratings for the second week of the new season had been posted, and Friday night had been cornered by NBC. Chico and the Man was the No. 1 show for the week, Sanford and Son No. 3. Apes, directly opposite, was No. 43.

Galen was leading astronauts Alan and Pete across the dry, stony bed of Malibu Creek, tracked by the camera as they scuttled away from the pursuing gorillas. A few yards downstream a deer emerged from the woods, surveyed the goings-on, gave the cervine equivalent of a shrug, then bounded across the creek and vanished among the cottonwoods and sycamores on the opposite bank. A visitor, watching it, said, “Beautiful!” A gorilla slumping next to him said, dispiritedly: “Why? Is a deer supposed to be good luck or something?”

Things picked up considerably at lunch time. It was Roddy McDowall’s 46th birthday. Eldon and Ronnie, the stunt gorillas, lugged McDowall out of his trailer, in a two-man fireman’s carry, to officiate over his birthday cake and open his present from the crew. Roddy was wearing a turquoise terrycloth jacket over his green chimp-tights, and violet shades over his sunken chimp-eyes. An ivory cigarette-holder protruded from his chimp-mouth. He had trouble extinguishing the birthday candles. “Blow harder,” somebody said and Roddy said, “Look, I don’t want to blow my face off!”

He was genuinely touched by his present: an inscribed silver wine bucket and a pair of matching wine cups. All that was missing, he noted, was a silver straw. The setting was eminently apropos. It was here, on the Century Ranch, 33 years ago, that Roddy McDowall became a movie star. The ranch was dressed up like a Welsh mining town then. The movie was “How Green Was My Valley.”

|

Then it was back to the usual routine on your usual ape-show location. Apes lined up with humans to draw their day’s travel pay. Apes, along with humans, hitched a ride back to the set on a prop truck. Other apes, stretching the lunch break to the fullest, stretched out to sunbathe, from the appliance down. Roddy McDowall was still hopping delightedly from crewperson to crewperson, thanking each one for the marvelous gift on his most marvelous birthday.

I had the feeling that someone was missing who could put the scene in its rightful perspective. I chose to think that he was there, Doctor Dolittle’s fugitive monkey, bug-eyed, hanging from a live-oak limb on top of the hill, looking down at the happy-birthday boy and crying, “Uncle!” |

|  |  |

|

|

|  |  |  | | BELOW: The feature as it originally appeared. |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|  |

|