|

|

|  |

|

|

|  |  |  |  |

|

|  |  |

|

|  |  |  | “Up Above the World So High”: a phrase from a nursery rhyme, deviating from the normal “Apes” titling format, and bringing with it an association with things past, a sense of innocence—and an acute sense of loss…

|

|  |

|

|

Up Above the World So High’s status as the final episode of the Planet of the Apes TV series would appear to be beyond doubt.

It was the last episode to be filmed (some time in early November 1974, to judge from the dates on the pages of the script’s final revisions—although a copy of the script I have seen has the date “27//11/74” handwritten across the cover indicating, perhaps, the date the editing or post-production was completed).

It not only features our three protagonists, but also marks one of the few occasions when both of the semi-regular supporting characters: Chief Councillor Zaius (portrayed by Booth Colman) and Chief of Security Urko (essayed by Mark Lenard) are present—albeit in brief, almost cameo appearances. They had only appeared together previously in four of the thirteen stories which make up the rest of the series’ run.

|

|

|

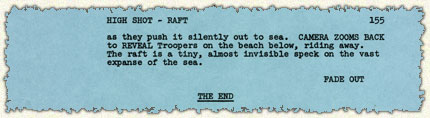

Most significant of all, perhaps, the tale’s final moments embody everything you would expect in a poignant “adieu,” as our heroes are shown drifting out to sea, accompanied by one of the most melancholic cues in the series’ musical library. Last, but far from least, in both the US and the UK, it was broadcast as the “final” episode.

There is some evidence to suggest, however, that it could have been (if you’ll pardon the expression) a very different story…

|

A study of the TV Guide listings for 1974 tells us that Up Above the World So High was originally scheduled to air on Friday, December 6th—seven days after the broadcast of The Cure. For some reason, however, the advertised transmission did not take place.

|

Had it gone ahead, the honour of bookending the series would have fallen to The Liberator, which would have been the only episode remaining (Although it is generally believed that the latter tale was never shown during the series’ Network run, the ratings data from the A. C. Nielsen Company shows that it did, in reality, go out in some states on December 6th. Supporting this is the fact that when the series aired in the U.K.—where the ITV running order echoed that of CBS—The Liberator was shown as the thirteenth episode, after The Cure.).

As it was, audiences in the land of the series’ birth finally got to fly Up Above the World So High on December 20th—two weeks later than originally advertised and—a December 27th rerun of Escape From Tomorrow notwithstanding—saw the story as the series’ final episode.

All of which raises the issue of why the December 6th transmission of the story was abandoned…

|

|

|

|

|  |  |  | The TV Guide listings for both the December 20th airing of Up Above the World So High, and the previous entry for the postponed December 6th broadcast.

|

|  |

|

|

Was it “bumped” from its original slot because something of urgent significance had to be shown instead? Or (as unlikely as it may seem) was a creative decision made to schedule it after The Liberator because it was more suited to the role of being the closing chapter of the saga?

Whatever the reason, the thought of any episode other than Up Above the World So High providing our final moments with Virdon, Burke and Galen is impossible to bear. On so many levels, the tale offers the best conclusion to their adventures that the circumstances of the series’ premature demise could have offered.

When I sat down to watch it for the first time, however—on Sunday, January 19th, 1975—I was anticipating something very different, and as the story began to unfold I was—at least at first—disappointed.

As the superb opening titles devised by The Jack Cole Film Group flickered into life, I was aware that the events I was about to witness would be the last I would see from the “Planet of the Apes”.

I had learned of the series’ cancellation a month previously, when it was mentioned as part of the Sunday Times’ December 22nd listing for The Tyrant. Consequently, when the same journal revealed the title of the concluding chapter on the day of its transmission, my imagination (such as it was) began to construct all manner of possibilites.

|

|

|  |  |  | Leuric’s glider. Not the key to the super-civilisation I was expecting…

|

|  |

|

|

Up Above the World So High…

Almost all the preceding “Apes” episodes been characterised by their use of the word “The…” as a prefix in their titles. The only stories to deviate from this had been Tomorrow’s Tide and the series debut, Escape from Tomorrow. The fact that this “final” offering also broke from the established “norm” seemed significant.

Adding weight to my speculations was the fact that a phrase from a nursery rhyme had been used to encapsulate the story’s events. With its lyricism and association with things past, it evoked the air of sorrow and reflection that a swansong demands.

|

|

|

Knowing, too, that at the heart of Virdon and Burke’s adventures lay a quest for a way to return to the stars, in the hope of finding a pathway to the past, the episode’s title, carrying implications of escaping the confines of earth, or of looking down at the world from the edge of space, seemed to suggest one thing: the possibility that Virdon would find the super-civilisation he had been looking for, and that this final chapter might conclude (at the very least) with the two astronauts departing for home.

As the first part of the story drew to a close, however, and we paused for the first commercial break, I was reluctantly beginning to entertain the thought that the story would not be offering any kind of resolution. The astronauts’ goal had never been mentioned, and there was not even a hint of the existence of the “super-civilisation.” I was, I suspected, watching a “regular” episode…

|

Subsequently, when the story resumed, and we saw Carsia arriving at Chatka to “interview” Leuric—accompanied by what is probably my favourite piece of music composed for the series—I experienced (I am only marginally ashamed to admit) an acute pang of dismay…

We were now one-third of our way through the story!

There were only forty minutes left!

Forty minutes!

Then, in those far-off, pre-“home entertainment” days, it would be over, and lost forever. Consigned to memory. I was suddenly conscious that time was rushing by, and I was powerless to stop it.

All I could do… was watch.

|

|

|

|

|  |  |  | Carsia arrives at Chatka garrison. The threads of the narrative are coming together—and the sands of time are running out…

|

|  |

|

|

With that realisation, I abandoned my preconceptions, and surrendered myself to the story that had been placed before me.

As it turned out, this was a joy.

Up Above the World So High is fun, and when you’re saying good-bye to people you’ve come to like and care about, it seems only right that your final moments with them should be enjoyable ones.

|

|

|  |  |  | Carsia. A complex, credible individual. Cold. Manipulative. Her outlook on life skewed by her belief in the superiority of her species. Arguably the most malevolent adversary the fugitives faced.

|

|  |

|

|

The story is imbued with an engaging lightheartedness that manifests itself in the characters (the unapologetically resolute inventor, Leuric, for example), in the dialogue and situations, and in the performances.

The writing is, I think, some of the best the series had. The characters are well delineated; their individual stories engaging and satisfying—and there are several tales being told here.

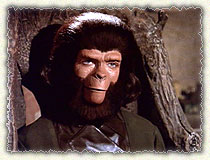

The female chimpanzee scientist, Carsia, is fascinating. She accomplishes with ease something even Zaius has struggled to do in the past: manipulates and betters Urko at a meeting of The High Council.

|

|

|

The scene in which she uses her status to drive the gorilla garrison commander, Konag, from his personal living quarters is wonderfully entertaining, and superby realised by the actors and director John Meredith Lucas. As the characters converse, their positions relative to Konag’s chair and desk are exchanged, mirroring the transformation in their status. The writers, to their credit, even find time to give “closure” to the sub-plot of the antagonism between the two when, towards the end of the story, we witness the gorilla commander relishing the opportunity to turn the tables on his tormentor…

|

As for the “regular” characters—our heroes—“Up Above the World So High” is home to some of their most memorable moments.

Galen’s discovery of the adhesive properties of glue is outstanding, and although we have often seen the renegade chimpanzee adamantly refuse to risk his life in one of Virdon and Burke’s strategems, only to subsequently accede to their entreaties, we have never seen it done as magnificently as it is done here when (in a beautifully performed and edited sequence) he is persuaded to be hurled from a clifftop aboard the glider the astronauts have constructed.

|

|

|

|

|  |  |  | “Boiled tree sap, and cornflour…”

|

|  |

|

|

|

|  |  |  | The courtship dance that takes place between Carsia and Galen, as the female chimpanzee discloses her attitudes and theories, is not described in the script.

|

|  |

|

|

Most enjoyable of all, perhaps, is observing Galen’s growing affection for Carsia, and his indignation at Burke’s letcherous (and all too accurate) insinuations—a development which McDowall brings to life with obvious relish.

Seeing this, I can understand why Roddy McDowall stated, in later years, that of all the simian “skins” he inhabited, Galen was his favourite…

There were some surprises, too. We saw how, even after all this time, Galen still retained some of the prejudices and unmoderated directness he exhibited when we first met him.

|

|

|

When Leuric’s single-mindedness leads to the capture of the renegade chimpanzee and himself, the incarcerated, injured inventor reflects morosely that, “I’m sorry. It’s all my fault.” In response, Galen unsympathetically voices the opinion that, “Of course it is!”—refusing to ease—or even recognise—the human’s feelings of guilt.

A good script, however, is nothing without good performances, and Up Above the World So High has those, nurtured by John Meredith Lucas’ inventive and sympathetic direction.

|

|

|

|

|  |  |  | Leuric helps Galen to reconnect with his contempt for humans.

|

|  |

|

|

The three lead actors work as hard as they always have, bringing their differing characters into focus with every line. It’s fascinating to read, for example, the scripted exchange between Virdon, Burke and Galen in the ruined temple on pages 32 and 33 of the episode’s Revised Final Draft (available on Hunter Goatley’s Apes site: Hunter’s Planet of the Apes Archive), during which they arrive at their decision to build the glider themselves. When the scene is viewed in the final, filmed episode, we can see so much was added, and so much was eliminated—and all for the better.

|

|

|  |  |  | A touching moment… Burke gives gives an extremely unhappy Galen a reasuring squeeze on his arm—after first delighting in his discomfort, of course.

|

|  |

|

|

In a similar vein, in the same draft, the scene in which Carsia reveals her chimpanzee supremacist theories to Galen is, as written, nothing more than several pages of exposition which the female scientist delivers from her chair. Little is suggested in the way of staging, and there is none of the seductive, “Tom Jones”-esque will they/won’t they “ballet” that we saw on screen.

There are some minor, telling embellishments to the story, too.

Two characters who are un-named in the script—the “Council Orang”and “Human Driver”—acquire names in the filmed episode.

|

|

|

Also: in the final seconds of the adventure, as our heroes begin to guide the raft out to sea, Burke laughs at Galen’s mal-de-mer, but then reaches out and squeezes the chimpanzee reassuringly on the arm—a gesture of affection that, given this is the last we moment we will share with these characters, tugs all the more strongly at the heartstrings.

In a tale of perfect peformances, however, special mention must be made of Martin Brooks’ delicious “Cookie Monster” portrayal of Konag. It is astonishing to reflect that this is the same actor who played the stolid Leander in The Surgeon, and the bland Rudy Wells in The Six Million Dollar Man series. Percy Rodriguez—who guest starred as Aboro in The Tyrant—is reported to have said that he found the anonymity of the appliances incredibly liberating as an actor, and Martin Brooks’s work on Apes certainly supports that.

|

Despite the story’s overall lightheartedness, however, Up Above the World So High is not without menace or drama. As always, events unfold beneath the storm clouds of the simian authorities’ domination and the threat of unrestrained violence that hangs over the human population. We see Leuric arrested, and hear Galen give voice to the likelihood of the inventor’s public execution. Most shocking of all, we witness the human’s unrestrained beating at the hands of the Chatka garrison’s gorilla guards…

All of which makes the story’s humourous moments more welcome, and our heroes’ (and Leuric’s) victory all the more meaningful.

|

|

|

|

|  |  |  | “We have no guest facilities! This is a troop garrison!” While Carsia conspires, Konag loses the plot—and Martin Brooks channels Sesame Street’s “Cookie Monster” to create one of Apes’ most memorable characters.

|

|  |

|

|

In terms of post-production, the selection of musical cues assembled to complete this final tale are almost a “greatest hits” compilation of the best of the scores written for the series, from the suspense-laden themes of Richard La Salle—originally contained within The Trap—to the stirring melodies of Earle Hagen carried by Tomorrow’s Tide, and the establishing flourishes and etherial coda provided by Lalo Schifrin for The Gladiators.

|

|

|  |  |  | Burke, Virdon and Galen turn tail—leaving their placemarkers behind them.

|

|  |

|

|

Which is not to say that the tale is without its faults, of course.

There are some conspicuous technical shortcomings which speak, perhaps, of pressure of time.

We can see visible placemarkers in the opening scenes by the wall on the coast, and the use of a plastic, “joke shop” fly for the moment when Galen demonstrates his (or rather Burke’s) “Expander” is… an unfortunate decision.

One can only assume that, on the day, the crew were unable to press into service a living example of the real thing.

|

|

|

There is also the curious case of Carsia’s chauffeur…

When the chimpanzee scientist arrives at Chatka, her carriage is driven by a white human male—portrayed by reknowned stunt arranger and performer Glenn Wilder. Yet, when she arrives at the clifftop for the story’s conclusion, there is an African-American human holding the reins…

Perhaps Wilder had other duties that day?

These shortcomings need to be balanced against the countless occasions where the production team succeeded, of course—and on a trivial note (and on the subject of echoes from the past) it seems appropriate to mention that in the background of Leuric’s workshop can be seen the elegant, angled bookcase that adorned Cornelius’ office in the original Apes movie…

As it is, those aspects of the production which fell short of what they could have been bother me less than a number of elements of the story itself.

|

For example, I have always been uncomfortably aware that it’s possible to categorise Up Above the World So High as a “gimmick” episode—one which owes its inception more to a then-current interest (“hang gliding”) rather than to a desire to tell a particular story.

Writers and script editors of Television series often seize on a popular fad as a way of attracting an audience and this, inevitably, results in them distorting the format of their particular show to accommodate the incompatible subject matter, and ties their tale to a particular moment in time—usually to its detriment.

I think that such criticism is inappropriate for Up Above the World So High, however, because the story has nothing to do with “hang gliding” as it was in 1974—the glider(s) simply provide legitimate “vehicles” (ouch!) for a story set in a post-apocalyptic world in which the secret of flight is being rediscovered.

|

|

|

|

|  |  |  | Konag makes his way towards Carsia’s carriage—and we see that the female scientist’s human chauffeur is not the one who brought her to Chatka…

|

|  |

|

|

Less easy to accomodate, however, is the issue of Zaius’ and Urko’s reaction to the news of that rediscovery…

When Konag brings the remains of Leuric’s glider before the High Council (in what would amount, really, to a “Roswell” moment for the simian society) neither Zaius nor Urko seem particularly concerned with the question of how this 31st-Century “Da Vinci” came to design and built his flying machine. Dismissing the glider as a “toy,” their only concern is removing it and him from society—until Casia mentions that, “It’s not widely known, but there is reason to believe that our ancestors… knew how to fly. There are references—vague but strongly suggestive—in remnants of books from the old days, before the world was almost destroyed.”

It is only then that the Chief Councillor and Chief of Security exhibit any real interest in Konag’s report, and exchange a significant glance.

Zaius comments, with emphasis, that, “Perhaps this human learned… from some book he found,” to which Urko adds, “If he has such a book, it is punishable by death; it could infect the other humans.”

It’s an effective, engaging moment because in their performances Booth Colman and Mark Lenard manage to convey the idea that only they understand the full significance of what the female scientist is saying; that any such book would be human in origin and that it represents a danger to simian authority.

|

|

|  |  |  | Zaius and Urko add weight to Carsia’s chimpanzee supremacist theories by failing to ask themselves where Leuric might have obtained his knowledge of aerodynamics…

|

|  |

|

|

The ape leaders’ concern over the book connects perfectly with sentiments they have expressed previously (in Escape from Tomorrow and The Surgeon)—and pays tribute to the degree to which the writers were maintaining consistency with what had gone before but there is something missing from this scene.

Given that the account of a flying human did not represent something new to the world of 3085, but rather something that had been a feature of earth’s past, we might have expected either Zaius or Urko to recognise the possibility that Leuric had been taught to fly by others who had flown: specifically, the two fugitive astronauts from the twentieth century who the apes already considered to be potential carriers of the “disease ”of ancient human knowledge.

|

|

|

The absence of any such discussion may be an oversight on the part of the writers, but I doubt it. I think it was done deliberately.

If our senior simians had even suspected Virdon and Burke’s involvement, Urko would have had to travel to Chatka to investigate, and events would have taken a very different direction to the ones we know. The elements that make Up Above the World So High unique and interesting—the point scoring between Carsia and Konag; the relationship between Galen and female scientist; the involvement of Virdon and Burke—would have been lost.

In the First Draft script of the episode, the gorilla Chief of Security did play a greater role in the proceedings, so the fact that subsequent reworkings of the narrative moved away from this suggests to me that the failure of Zaius and Urko to consider the fugitives’ involvement in the events at Chatka was a conscious decision on the part of the writers, enabling them to take the story in the direction they wanted—and hoping that the audience wouldn’t notice any complacency on the part of the simian authorities.

While some aspects of the story improved beyond measure in subsequent rewrites, however, one crucial aspect suffered: the attitude of Virdon and Burke towards Leuric, and their motives for helping him.

In the completed episode, Leuric—shortly after being resuced by the fugitives—demonstrates his “wind tunnel” to them. While paying lip-service to the significance of the inventor’s accomplishments, the two astronauts then attempt to discourage him from realising his dream.

Virdon, examining Leuric’s miniature prototype, says—in an incredibly patronising moment, “What you’ve constructed is a kind of… ‘glider’—which is a remarkable achievement—but it’s a dead end. Where d’ y’ go with it?”

“Up into the sky!” cries Leuric.

“Invent a new plough or something,” Burke tells him.

I’m with Leuric on this one.

For me, it goes against the grain of the theme of the series for the men from the past to be telling one of the members of the human slave community to “play it safe,” and to stifle his intellect and curtail his ambitions.

Surely, this is what the apes are doing—supressing the rights of the human inhabitants of the planet and trying to convince them they are without virtue and inferior to their simian masters? For Virdon and Burke to be party to that is appalling! The astronauts should be championing the cause of human freedom and equality, and encouraging Leuric—and all humans—to better themselves! As, in fact, they had done with Miro and the people of Borak in The Liberator!

|

Secondly, although there are some (including actor Mark Lenard) who dislike the series’ preoccupation with plots in which the astronauts use the science of the past to resolve a problem faced by the people of the future, for me, this need not have been an issue—except that its use here robs the story of its weight. The glider that carries Leuric into the air at the story’s conclusion has been designed and built for him by Virdon and Burke—and is being piloted by Galen, who has already flown the glider during the test. Consequently, the human inventor’s euphoric, air-borne cry of, “I made it happen! What nobody ever did before!” is meaningless.

The glider should have been Leuric’s, as should the achievement.

|

|

|

|

|  |  |  | Virdon tells Leuric to abandon his dreams and stop reaching for the stars—fine talk for an astronaut and would-be champion of human emancipation…

|

|  |

|

|

In fairness to the writers, in the first draft of the story Virdon and Burke assist Leuric not from any sense of superiority, but in order to save his life. The aspiring aeronaut has been incarcerated by Carsian, and given five days to construct a glider that will fly. Realising that their fellow human doesn’t have the knowledge to accomplish what the apes expect of him in that time, the astronauts undertake the work.

In subsequent rewrites, however, as the personalities of the characters and the pattern of events around them shifted, Virdon and Burke’s motives and attitudes were reformed to the point where they became less commendable. Given time, perhaps, this could and would have been corrected.

Pressure of time—both in terms of the forty-eight minutes available for the telling of the story, and the three week window for writing it—undoubtedly prevented the writers from exploring and elucidating every aspect of the story—which probably accounts, also, for what amounts to one of the tale’s major lapses in logic…

Carsia is planning to blow up the High Council. Galen knows this. So, when Galen is captured during the abortive attempt to destory the glider, why doesn’t he tell Konag of the female scientist’s murderous ambitions? Is it because there is a danger he would be exposed as Galen, the fugitive, thereby placing Virdon and Burke in jeopardy also?

If we accept this, it still leaves us with the issue of why Carsia isn’t worried that “Protus”—having shown he opposes her plans—will implicate her! She, after all, is unaware that he has a secret which prevents him from revealing all he knows…

It’s such a conspicuous problem that, I suspect, it must have been recognised—and to have addressed it would have required yet another rewrite. Perhaps there simply wasn’t time.

Which brings me, finally, to an aspect of the tale that does expose a flaw in the production team’s thinking, and suggests that they were giving little serious consideration to defining the level of technology that the apes possessed: the role played by the Galen-Burke “Expander.”

The events of Up Above the World So High place considerable emphasis on the fact that both Galen and Carsia (who is one of the apes’ senior scientists) have never seen a magnifying glass before. In fact, judging by the scene in which Galen asks about the “strange rock” in Leuric’s workshop, our favourite renegade chimpanzee has never encountered glass before!

In The Surgeon, however, we see Burke using a microscope to examine blood samples in the Central City Medical Centre, and the female chimpanzee scientist at the heart of The Interrogation —Wanda—wears spectacles…

So: do the apes understand the principles of optics, or not?

|

|

|  |  |  | Leuric—fearless visionary and artisan—employs an ancient plane to shape a contemporary one.

|

|  |

|

|

The series’ “Bible” does contain some justification for this apparent contradiction. It talks of “a world that is an amalgam of medieval times and the near future; of relics from past civilizations and manifestations of future ones.”

This is echoed in Arthur Browne, Jr.’s First Draft of the script for Up Above the World So High, in which he describes the Chatka garrison workshop as, “Superbly equipped, a kind of museum of assorted tools used by humanity way back in the Nineteenth and Twentieth centuries.”

|

|

|

Which means that the microscope Burke uses in The Surgeon and the spectacles worn by Wanda in The Interrogation could be artefacts from the days when humans ruled the world—and yet none of this is explained in the dialogue.

Perhaps, for the sake of credibility, it should.

What is more of a “sticking point,” I feel, is having to accept that the ape civilisation is bereft of adhesives—and the scene where Carsia attempts to use a plane to hammer a nail into a bench is, well, a little clumsy—on every level.

In truth, however, the issues I have noted really don’t mar the appeal of the story, and most of them only become noticable with repreated viewings—or an analysis like this one. Looking back at Up Above the World So High from the vantage point of today, the tale’s moments of weakness fade into nothing when measured against the areas where it succeeds.

What stands out, almost forty years later, is how stylish it is; from Gerald Perry Finnerman’s gritty, stroboscopic photography, to the music from Schifrin, Hagen and La Salle, to the inventive contributions from the cast and, underpinning it all, the care and imagination that went into the shaping of the story—even though the team knew that this was to be the end of Virdon, Burke and Galen’s journey.

Here we have our final installment and yet—in the personality of Carsia and the “chimpanzee supremacist” group she belongs to—it offers us a new aspect to the simian society, one which contains the potential for a recurring menace, and the promise of a rematch that would remain unfulfilled…

Which raises, once again, the question of whether or not the story was designed to be the series finale.

Undoubtedly, when Shimon Wilcelberg first pitched it, it was not—but it’s impossible not to conclude that it was eventually fashioned with that role in mind.

The original setting for the tale was inland, and concluded with Leuric’s death, and Virdon, Burke and Galen riding away from us on horseback, heading for the hills in a manner that was reminiscent of the conclusions to most of their previous adventures. Was Leuric’s life preserved, and the location switched to the coast, to provide us with a much more upbeat resolution and the symbolic imagery described in the Revised Final Draft of the screenplay:

|

|  |

John Meredith Lucas’ realisation of that final shot is so beautifully eloquent of a sad “Fare Well” that it has to be intentional: a long, slow pan from left to right, that begins with the horses and carriage of the departing Carsia, Konag and troopers, then drifts languidly over the edge of the clifftop, to linger on the small but significant spec of the raft moving out across the surface of the ocean.

The scene is presented without a word of dialogue. As the rattle of the departing horses and waggons fades, Lalo Shifrin’s evocative Gladiators cue, “A Beginning”, rises up to underscore what had become, all too soon, “The End”…

|

|

|

|

|  |  |  | “It flew like a bird! I knew it would! I could have stayed up forever!” Ah. If only…

|

|  |

|

|

|  | |

|

|

|

|

|

|  |

|